Event (probability theory)

In probability theory, an event is a set of outcomes (a subset of the sample space) to which a probability is assigned.[1] Typically, when the sample space is finite, any subset of the sample space is an event (i.e. all elements of the power set of the sample space are defined as events). However, this approach does not work well in cases where the sample space is uncountably infinite, most notably when the outcome is a real number. So, when defining a probability space it is possible, and often necessary, to exclude certain subsets of the sample space from being events (see Events in probability spaces, below).

Contents |

A simple example

If we assemble a deck of 52 playing cards with no jokers, and draw a single card from the deck, then the sample space is a 52-element set, as each card is a possible outcome. An event, however, is any subset of the sample space, including any singleton set (an elementary event), the empty set (an impossible event, with probability zero) and the sample space itself (a certain event, with probability one). Other events are proper subsets of the sample space that contain multiple elements. So, for example, potential events include:

- "Red and black at the same time without being a joker" (0 elements),

- "The 5 of Hearts" (1 element),

- "A King" (4 elements),

- "A Face card" (12 elements),

- "A Spade" (13 elements),

- "A Face card or a red suit" (32 elements),

- "A card" (52 elements).

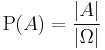

Since all events are sets, they are usually written as sets (e.g. {1, 2, 3}), and represented graphically using Venn diagrams. Given that each outcome in the sample space Ω is equally likely, the probability of an event A is

this rule can readily be applied to each of the example events above.

Events in probability spaces

Defining all subsets of the sample space as events works well when there are only finitely many outcomes, but gives rise to problems when the sample space is infinite. For many standard probability distributions, such as the normal distribution, the sample space is the set of real numbers or some subset of the real numbers. Attempts to define probabilities for all subsets of the real numbers run into difficulties when one considers 'badly-behaved' sets, such as those that are nonmeasurable. Hence, it is necessary to restrict attention to a more limited family of subsets. For the standard tools of probability theory, such as joint and conditional probabilities, to work, it is necessary to use a σ-algebra, that is, a family closed under complementation and countable unions of its members. The most natural choice is the Borel measurable set derived from unions and intersections of intervals. However, the larger class of Lebesgue measurable sets proves more useful in practice.

In the general measure-theoretic description of probability spaces, an event may be defined as an element of a selected σ-algebra of subsets of the sample space. Under this definition, any subset of the sample space that is not an element of the σ-algebra is not an event, and does not have a probability. With a reasonable specification of the probability space, however, all events of interest are elements of the σ-algebra.

A note on notation

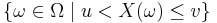

Even though events are subsets of some sample space Ω, they are often written as propositional formulas involving random variables. For example, if X is a real-valued random variable defined on the sample space Ω, the event

can be written more conveniently as, simply,

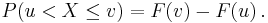

This is especially common in formulas for a probability, such as

The set u < X ≤ v is an example of an inverse image under the mapping X because ![\omega \in X^{-1}((u, v])](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/9425e505585bd4158841c2cea533bfbb.png) if and only if

if and only if  .

.

See also

Notes

- ^ Leon-Garcia, Alberto. Probability, Statistics and Random Processes for Electrical Engineering. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2008. Print.